[a couple of paragraphs from an unfinished review of World on a Wire, intended to coincide with the film's week-long run at the Museum of Modern Art in New York earlier this month]

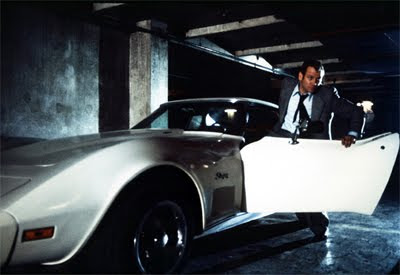

[a couple of paragraphs from an unfinished review of World on a Wire, intended to coincide with the film's week-long run at the Museum of Modern Art in New York earlier this month]The only starring role Fassbinder would give occasional company player Klaus Löwitsch, the lead in World on a Wire is Fred Stiller, a computer scientist with the mannerisms (and manners) of a pulp detective. A drinking game could be invented based on the number of times he grabs characters by the lapels (take two shots if he then pushes them against a wall or throws them against a table). Like coolcat sourpuss Jean-Louis Trintignant (to whom he bears a passing resemblance), Löwitsch expresses suspicion, fear, anger and shock though varying degrees of sullenness. He has an Eddie Munster-like widow’s peak that creeps up from under the brim of his fedora and the sort of intensity that, in film history, is the provenance of shorter men.

...

Here’s a rule of thumb a lot of cinephiles learn pretty early on: what looks good on a big screen doesn’t always look good on a small one, but what looks good on a small screen will always look good on a big one.

No surprise then that some of best revivals to come to theaters in the last few years – Out 1, Berlin Alexanderplatz and now World on a Wire – were all originally conceived for television. Though Jacques Rivette had to make an edited-down theatrical version for his film to get shown, Fassbinder shot and edited Berlin Alexanderplatz and World on a Wire exclusively for TV (he even entertained plans of remaking Berlin Alexanderplatz as a theatrically-shown feature with an international cast). On the small screen of a TV or a laptop, it's easier to grasp the geometric design of an image. At the expense of the details of mise-en-scene, the most rudimentary elements of framing and editing make themselves more obvious, a fact very few people seem to harness (Jack Webb was a notable exception). Like Roberto Rossellini, Fassbinder understood this.

No surprise then that some of best revivals to come to theaters in the last few years – Out 1, Berlin Alexanderplatz and now World on a Wire – were all originally conceived for television. Though Jacques Rivette had to make an edited-down theatrical version for his film to get shown, Fassbinder shot and edited Berlin Alexanderplatz and World on a Wire exclusively for TV (he even entertained plans of remaking Berlin Alexanderplatz as a theatrically-shown feature with an international cast). On the small screen of a TV or a laptop, it's easier to grasp the geometric design of an image. At the expense of the details of mise-en-scene, the most rudimentary elements of framing and editing make themselves more obvious, a fact very few people seem to harness (Jack Webb was a notable exception). Like Roberto Rossellini, Fassbinder understood this.

No comments:

Post a Comment